Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital ensures health care quality with innovations, technology

Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital ensures health care quality with innovations, technology

A male patient visited a privately-owned clinic in a community in northern Bangkok and complained to a doctor he had suffered abdominal pains for a couple of weeks.

A preliminary diagnosis was diarrhoea; but the doctor still thought the patient needed to consult a specialist at Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital (BAH).

It took the doctor a few minutes to key into his computer the diagnosis, medicines prescribed and a request for an appointment with a specialist for the patient. This information was sent online instantly as soon as the doctor pressed the save and send buttons on the computer’s screen.

The patient got his medicines and went home waiting for a notification to be sent to his smartphone regarding the confirmation of his appointment with a specialist at BAH. The information recorded at the clinic about the diagnosis of his illness and medicines prescribed were already sent to his phone via an application called BAH Connect.

Later in the afternoon, when BAH regularly responded to specialist appointment requests received each day, the appointment request sent by the clinic was confirmed. The confirmed appointment was instantly sent to the clinic and the patient online.

The following day, the patient visited BAH without having to go back to the clinic for a referral document. And all he had to do at the hospital’s outpatient ward was allowing a nurse to check his vital signs and recorded them to an electronic file of his medical record, which was later retrieved by the specialist he saw.

As it turned out, the specialist ruled it was acute gastroenteritis that caused his illness and the doctor wanted to follow up on his condition in the next appointment with him.

All new information – the new diagnosis, laboratory test results, new medicines prescribed and the new appointment – was immediately sent online to both the clinic and the patient’s smartphone.

And that is how the so-called e-Referral system, launched in 2016 and now linked also with the BAH Connect mobile app, of BAH’s primary care network works.

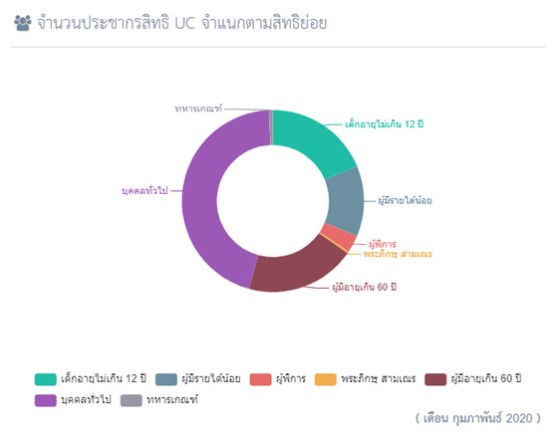

The BAH’s primary care network, operated under the country’s universal health coverage (UHC) scheme that covers about 48 million Thais or about 75% of the entire population, now consists of 25 privately-owned clinics.

The network now takes care of about 150,000 people under the UHC in five northern Bangkok districts, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong Pajaree, director of BAH.

Two clinics had been excluded from the network after they failed an annual health care quality audit, he said.

Back in 2002, the nationwide implementation of the UHC came as a real headache to BAH. As a teritiary referral hospital, BAH didn’t have any general practitioner (GP) but it was required to deliver primary care to patients under the UHC. The reason is it is the only large state-run health care facility in this particular area of the capital.

As soon as the UHC policy was implemented, BAH found its outpatient ward suddenly becoming overcrowded, while its specialists were forced to take an extra workload of primary care services, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

And since BAH is a health care facility of the air force, it isn’t permitted to buy or rent a building to set up its own primary health care facilities outside air force’ areas, he said.

“We had trouble trying to cope with these problems for many years. The outpatient ward was crowded with 500 to 600 patients a day. No one was happy. There were lots of complaints from both patients and hospital staff,” he said.

Thinking outside the box, he eventually saw a good potential in those many privately-owned clinics and came up with an idea of forming a primary care network with them.

The hospital in the beginning aimed to recruit only between seven and ten clinics into the network; but up to 30 clinics had applied, he said.

A total of 27 clinics were then chosen for implementing the primary care network plan, which began in 2006 and became in full operation in 2007.

These clinics are paid an annual budget of between 700 baht and 1,200 baht per head of the people they take care of under the UHC, said Dr Weraphan Leethanakul, director of the National Health Security Office’s Region 13 office in Bangkok.

The clinics are also entitled to receiving extra budget for additional health promotion and prevention work in communities if they are willing to do, he said.

Prem Pracha Medical Clinic, one of the 25 clinics in the BAH’s primary care network, for instance, now takes care of 9,754 people, or about 18% of the population registered under the UHC in the areas covered by BAH, he said.

Currently, Bangkok has about 279 primary care units and 40 hospitals under the UHC, he said.

With the primary care network in place, the number of outpatients at BAH had dramatically dropped from between 500 and 600 a day to only 80 a day, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

After all, a major problem remained. The hospital still struggled to deal with about 180,000 patient referrals a year. Each referral consumed a lot of time on both the patient and the hospital sides due to the amount of paperwork involved.

“The referral paperwork was something that could actually be completed in a minute; but it in reality took more than an hour to get done at the time,” he said.

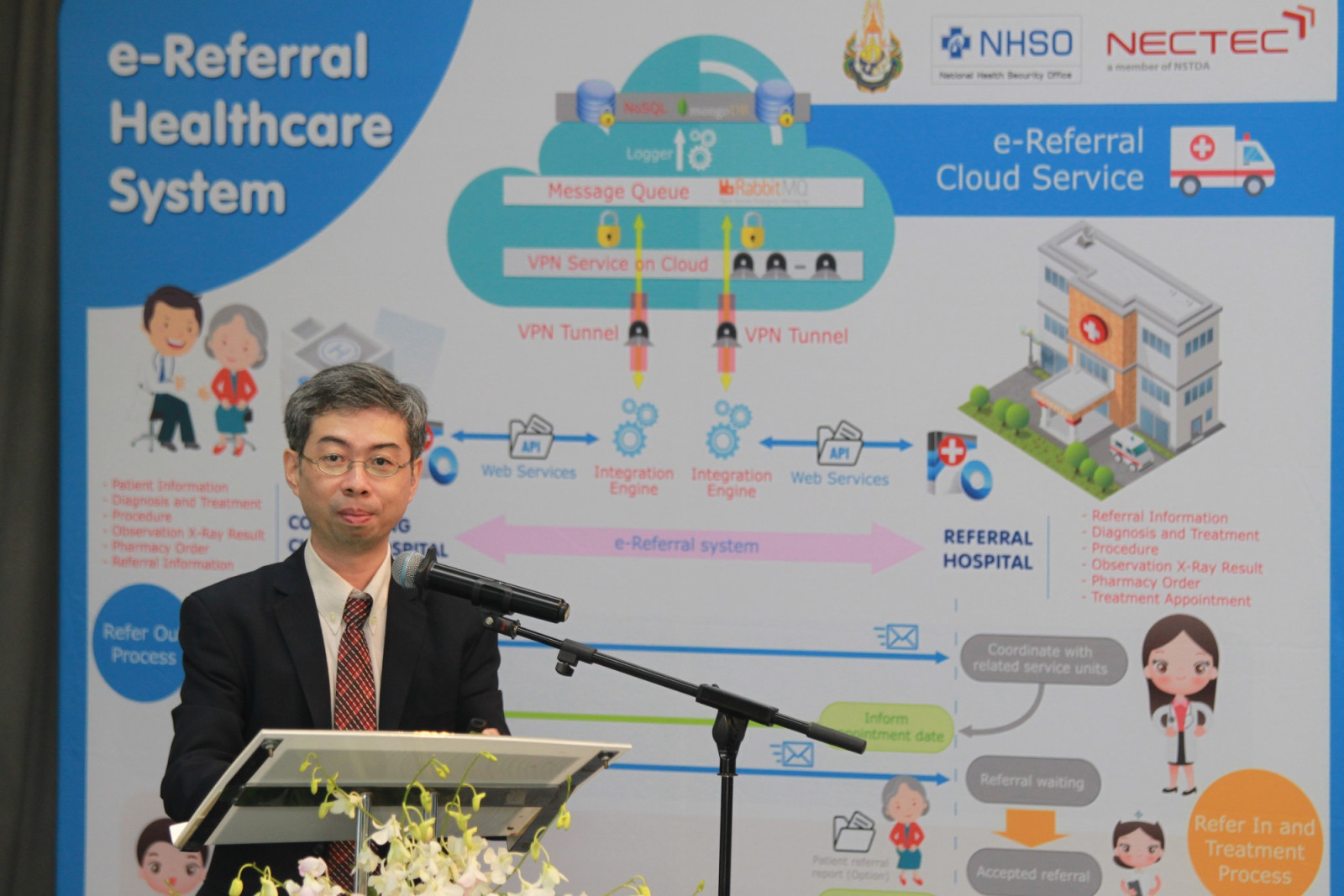

BAH had therefore in 2016 begun collaborating with the NHSO and the National Electronics and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC) to develop an electronic patient referral system.

The e-Referral is a cloud-based system that helps cut paperwork and save a great deal of time and money for both patients and the health care facilities, said Sarun Sumriddetchkajorn, a deputy executive director of NECTEC.

As well, the e-Referral system helps cut unnecessary travelling costs of the patients by at least 10 million baht a year and save about 77 minutes per patient in waiting time, said Vice Marshal Taweepong.

BAH now expects to next win permission to gain full access to health care databases of the 25 clinics under its primary care network via the e-Referral system and use artificial intelligence (AI) to better access their health care performance, he said.

“Quality in health care is our goal,” he said.

////////////30 January 2020

A male patient visited a privately-owned clinic in a community in northern Bangkok and complained to a doctor he had suffered abdominal pains for a couple of weeks.

A preliminary diagnosis was diarrhoea; but the doctor still thought the patient needed to consult a specialist at Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital (BAH).

It took the doctor a few minutes to key into his computer the diagnosis, medicines prescribed and a request for an appointment with a specialist for the patient. This information was sent online instantly as soon as the doctor pressed the save and send buttons on the computer’s screen.

The patient got his medicines and went home waiting for a notification to be sent to his smartphone regarding the confirmation of his appointment with a specialist at BAH. The information recorded at the clinic about the diagnosis of his illness and medicines prescribed were already sent to his phone via an application called BAH Connect.

Later in the afternoon, when BAH regularly responded to specialist appointment requests received each day, the appointment request sent by the clinic was confirmed. The confirmed appointment was instantly sent to the clinic and the patient online.

The following day, the patient visited BAH without having to go back to the clinic for a referral document. And all he had to do at the hospital’s outpatient ward was allowing a nurse to check his vital signs and recorded them to an electronic file of his medical record, which was later retrieved by the specialist he saw.

As it turned out, the specialist ruled it was acute gastroenteritis that caused his illness and the doctor wanted to follow up on his condition in the next appointment with him.

All new information – the new diagnosis, laboratory test results, new medicines prescribed and the new appointment – was immediately sent online to both the clinic and the patient’s smartphone.

And that is how the so-called e-Referral system, launched in 2016 and now linked also with the BAH Connect mobile app, of BAH’s primary care network works.

The BAH’s primary care network, operated under the country’s universal health coverage (UHC) scheme that covers about 48 million Thais or about 75% of the entire population, now consists of 25 privately-owned clinics.

The network now takes care of about 150,000 people under the UHC in five northern Bangkok districts, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong Pajaree, director of BAH.

Two clinics had been excluded from the network after they failed an annual health care quality audit, he said.

Back in 2002, the nationwide implementation of the UHC came as a real headache to BAH. As a teritiary referral hospital, BAH didn’t have any general practitioner (GP) but it was required to deliver primary care to patients under the UHC. The reason is it is the only large state-run health care facility in this particular area of the capital.

As soon as the UHC policy was implemented, BAH found its outpatient ward suddenly becoming overcrowded, while its specialists were forced to take an extra workload of primary care services, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

And since BAH is a health care facility of the air force, it isn’t permitted to buy or rent a building to set up its own primary health care facilities outside air force’ areas, he said.

“We had trouble trying to cope with these problems for many years. The outpatient ward was crowded with 500 to 600 patients a day. No one was happy. There were lots of complaints from both patients and hospital staff,” he said.

Thinking outside the box, he eventually saw a good potential in those many privately-owned clinics and came up with an idea of forming a primary care network with them.

The hospital in the beginning aimed to recruit only between seven and ten clinics into the network; but up to 30 clinics had applied, he said.

A total of 27 clinics were then chosen for implementing the primary care network plan, which began in 2006 and became in full operation in 2007.

These clinics are paid an annual budget of between 700 baht and 1,200 baht per head of the people they take care of under the UHC, said Dr Weraphan Leethanakul, director of the National Health Security Office’s Region 13 office in Bangkok.

The clinics are also entitled to receiving extra budget for additional health promotion and prevention work in communities if they are willing to do, he said.

Prem Pracha Medical Clinic, one of the 25 clinics in the BAH’s primary care network, for instance, now takes care of 9,754 people, or about 18% of the population registered under the UHC in the areas covered by BAH, he said.

Currently, Bangkok has about 279 primary care units and 40 hospitals under the UHC, he said.

With the primary care network in place, the number of outpatients at BAH had dramatically dropped from between 500 and 600 a day to only 80 a day, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

After all, a major problem remained. The hospital still struggled to deal with about 180,000 patient referrals a year. Each referral consumed a lot of time on both the patient and the hospital sides due to the amount of paperwork involved.

“The referral paperwork was something that could actually be completed in a minute; but it in reality took more than an hour to get done at the time,” he said.

BAH had therefore in 2016 begun collaborating with the NHSO and the National Electronics and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC) to develop an electronic patient referral system.

The e-Referral is a cloud-based system that helps cut paperwork and save a great deal of time and money for both patients and the health care facilities, said Sarun Sumriddetchkajorn, a deputy executive director of NECTEC.

As well, the e-Referral system helps cut unnecessary travelling costs of the patients by at least 10 million baht a year and save about 77 minutes per patient in waiting time, said Vice Marshal Taweepong.

BAH now expects to next win permission to gain full access to health care databases of the 25 clinics under its primary care network via the e-Referral system and use artificial intelligence (AI) to better access their health care performance, he said.

“Quality in health care is our goal,” he said.

////////////30 January 2020

IN DEPTH

Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital ensures health care quality with innovations, technology

Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital ensures health care quality with innovations, technology

A male patient visited a privately-owned clinic in a community in northern Bangkok and complained to a doctor he had suffered abdominal pains for a couple of weeks.

A preliminary diagnosis was diarrhoea; but the doctor still thought the patient needed to consult a specialist at Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital (BAH).

It took the doctor a few minutes to key into his computer the diagnosis, medicines prescribed and a request for an appointment with a specialist for the patient. This information was sent online instantly as soon as the doctor pressed the save and send buttons on the computer’s screen.

The patient got his medicines and went home waiting for a notification to be sent to his smartphone regarding the confirmation of his appointment with a specialist at BAH. The information recorded at the clinic about the diagnosis of his illness and medicines prescribed were already sent to his phone via an application called BAH Connect.

Later in the afternoon, when BAH regularly responded to specialist appointment requests received each day, the appointment request sent by the clinic was confirmed. The confirmed appointment was instantly sent to the clinic and the patient online.

The following day, the patient visited BAH without having to go back to the clinic for a referral document. And all he had to do at the hospital’s outpatient ward was allowing a nurse to check his vital signs and recorded them to an electronic file of his medical record, which was later retrieved by the specialist he saw.

As it turned out, the specialist ruled it was acute gastroenteritis that caused his illness and the doctor wanted to follow up on his condition in the next appointment with him.

All new information – the new diagnosis, laboratory test results, new medicines prescribed and the new appointment – was immediately sent online to both the clinic and the patient’s smartphone.

And that is how the so-called e-Referral system, launched in 2016 and now linked also with the BAH Connect mobile app, of BAH’s primary care network works.

The BAH’s primary care network, operated under the country’s universal health coverage (UHC) scheme that covers about 48 million Thais or about 75% of the entire population, now consists of 25 privately-owned clinics.

The network now takes care of about 150,000 people under the UHC in five northern Bangkok districts, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong Pajaree, director of BAH.

Two clinics had been excluded from the network after they failed an annual health care quality audit, he said.

Back in 2002, the nationwide implementation of the UHC came as a real headache to BAH. As a teritiary referral hospital, BAH didn’t have any general practitioner (GP) but it was required to deliver primary care to patients under the UHC. The reason is it is the only large state-run health care facility in this particular area of the capital.

As soon as the UHC policy was implemented, BAH found its outpatient ward suddenly becoming overcrowded, while its specialists were forced to take an extra workload of primary care services, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

And since BAH is a health care facility of the air force, it isn’t permitted to buy or rent a building to set up its own primary health care facilities outside air force’ areas, he said.

“We had trouble trying to cope with these problems for many years. The outpatient ward was crowded with 500 to 600 patients a day. No one was happy. There were lots of complaints from both patients and hospital staff,” he said.

Thinking outside the box, he eventually saw a good potential in those many privately-owned clinics and came up with an idea of forming a primary care network with them.

The hospital in the beginning aimed to recruit only between seven and ten clinics into the network; but up to 30 clinics had applied, he said.

A total of 27 clinics were then chosen for implementing the primary care network plan, which began in 2006 and became in full operation in 2007.

These clinics are paid an annual budget of between 700 baht and 1,200 baht per head of the people they take care of under the UHC, said Dr Weraphan Leethanakul, director of the National Health Security Office’s Region 13 office in Bangkok.

The clinics are also entitled to receiving extra budget for additional health promotion and prevention work in communities if they are willing to do, he said.

Prem Pracha Medical Clinic, one of the 25 clinics in the BAH’s primary care network, for instance, now takes care of 9,754 people, or about 18% of the population registered under the UHC in the areas covered by BAH, he said.

Currently, Bangkok has about 279 primary care units and 40 hospitals under the UHC, he said.

With the primary care network in place, the number of outpatients at BAH had dramatically dropped from between 500 and 600 a day to only 80 a day, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

After all, a major problem remained. The hospital still struggled to deal with about 180,000 patient referrals a year. Each referral consumed a lot of time on both the patient and the hospital sides due to the amount of paperwork involved.

“The referral paperwork was something that could actually be completed in a minute; but it in reality took more than an hour to get done at the time,” he said.

BAH had therefore in 2016 begun collaborating with the NHSO and the National Electronics and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC) to develop an electronic patient referral system.

The e-Referral is a cloud-based system that helps cut paperwork and save a great deal of time and money for both patients and the health care facilities, said Sarun Sumriddetchkajorn, a deputy executive director of NECTEC.

As well, the e-Referral system helps cut unnecessary travelling costs of the patients by at least 10 million baht a year and save about 77 minutes per patient in waiting time, said Vice Marshal Taweepong.

BAH now expects to next win permission to gain full access to health care databases of the 25 clinics under its primary care network via the e-Referral system and use artificial intelligence (AI) to better access their health care performance, he said.

“Quality in health care is our goal,” he said.

////////////30 January 2020

A male patient visited a privately-owned clinic in a community in northern Bangkok and complained to a doctor he had suffered abdominal pains for a couple of weeks.

A preliminary diagnosis was diarrhoea; but the doctor still thought the patient needed to consult a specialist at Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital (BAH).

It took the doctor a few minutes to key into his computer the diagnosis, medicines prescribed and a request for an appointment with a specialist for the patient. This information was sent online instantly as soon as the doctor pressed the save and send buttons on the computer’s screen.

The patient got his medicines and went home waiting for a notification to be sent to his smartphone regarding the confirmation of his appointment with a specialist at BAH. The information recorded at the clinic about the diagnosis of his illness and medicines prescribed were already sent to his phone via an application called BAH Connect.

Later in the afternoon, when BAH regularly responded to specialist appointment requests received each day, the appointment request sent by the clinic was confirmed. The confirmed appointment was instantly sent to the clinic and the patient online.

The following day, the patient visited BAH without having to go back to the clinic for a referral document. And all he had to do at the hospital’s outpatient ward was allowing a nurse to check his vital signs and recorded them to an electronic file of his medical record, which was later retrieved by the specialist he saw.

As it turned out, the specialist ruled it was acute gastroenteritis that caused his illness and the doctor wanted to follow up on his condition in the next appointment with him.

All new information – the new diagnosis, laboratory test results, new medicines prescribed and the new appointment – was immediately sent online to both the clinic and the patient’s smartphone.

And that is how the so-called e-Referral system, launched in 2016 and now linked also with the BAH Connect mobile app, of BAH’s primary care network works.

The BAH’s primary care network, operated under the country’s universal health coverage (UHC) scheme that covers about 48 million Thais or about 75% of the entire population, now consists of 25 privately-owned clinics.

The network now takes care of about 150,000 people under the UHC in five northern Bangkok districts, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong Pajaree, director of BAH.

Two clinics had been excluded from the network after they failed an annual health care quality audit, he said.

Back in 2002, the nationwide implementation of the UHC came as a real headache to BAH. As a teritiary referral hospital, BAH didn’t have any general practitioner (GP) but it was required to deliver primary care to patients under the UHC. The reason is it is the only large state-run health care facility in this particular area of the capital.

As soon as the UHC policy was implemented, BAH found its outpatient ward suddenly becoming overcrowded, while its specialists were forced to take an extra workload of primary care services, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

And since BAH is a health care facility of the air force, it isn’t permitted to buy or rent a building to set up its own primary health care facilities outside air force’ areas, he said.

“We had trouble trying to cope with these problems for many years. The outpatient ward was crowded with 500 to 600 patients a day. No one was happy. There were lots of complaints from both patients and hospital staff,” he said.

Thinking outside the box, he eventually saw a good potential in those many privately-owned clinics and came up with an idea of forming a primary care network with them.

The hospital in the beginning aimed to recruit only between seven and ten clinics into the network; but up to 30 clinics had applied, he said.

A total of 27 clinics were then chosen for implementing the primary care network plan, which began in 2006 and became in full operation in 2007.

These clinics are paid an annual budget of between 700 baht and 1,200 baht per head of the people they take care of under the UHC, said Dr Weraphan Leethanakul, director of the National Health Security Office’s Region 13 office in Bangkok.

The clinics are also entitled to receiving extra budget for additional health promotion and prevention work in communities if they are willing to do, he said.

Prem Pracha Medical Clinic, one of the 25 clinics in the BAH’s primary care network, for instance, now takes care of 9,754 people, or about 18% of the population registered under the UHC in the areas covered by BAH, he said.

Currently, Bangkok has about 279 primary care units and 40 hospitals under the UHC, he said.

With the primary care network in place, the number of outpatients at BAH had dramatically dropped from between 500 and 600 a day to only 80 a day, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

After all, a major problem remained. The hospital still struggled to deal with about 180,000 patient referrals a year. Each referral consumed a lot of time on both the patient and the hospital sides due to the amount of paperwork involved.

“The referral paperwork was something that could actually be completed in a minute; but it in reality took more than an hour to get done at the time,” he said.

BAH had therefore in 2016 begun collaborating with the NHSO and the National Electronics and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC) to develop an electronic patient referral system.

The e-Referral is a cloud-based system that helps cut paperwork and save a great deal of time and money for both patients and the health care facilities, said Sarun Sumriddetchkajorn, a deputy executive director of NECTEC.

As well, the e-Referral system helps cut unnecessary travelling costs of the patients by at least 10 million baht a year and save about 77 minutes per patient in waiting time, said Vice Marshal Taweepong.

BAH now expects to next win permission to gain full access to health care databases of the 25 clinics under its primary care network via the e-Referral system and use artificial intelligence (AI) to better access their health care performance, he said.

“Quality in health care is our goal,” he said.

////////////30 January 2020

Events

Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital ensures health care quality with innovations, technology

Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital ensures health care quality with innovations, technology

A male patient visited a privately-owned clinic in a community in northern Bangkok and complained to a doctor he had suffered abdominal pains for a couple of weeks.

A preliminary diagnosis was diarrhoea; but the doctor still thought the patient needed to consult a specialist at Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital (BAH).

It took the doctor a few minutes to key into his computer the diagnosis, medicines prescribed and a request for an appointment with a specialist for the patient. This information was sent online instantly as soon as the doctor pressed the save and send buttons on the computer’s screen.

The patient got his medicines and went home waiting for a notification to be sent to his smartphone regarding the confirmation of his appointment with a specialist at BAH. The information recorded at the clinic about the diagnosis of his illness and medicines prescribed were already sent to his phone via an application called BAH Connect.

Later in the afternoon, when BAH regularly responded to specialist appointment requests received each day, the appointment request sent by the clinic was confirmed. The confirmed appointment was instantly sent to the clinic and the patient online.

The following day, the patient visited BAH without having to go back to the clinic for a referral document. And all he had to do at the hospital’s outpatient ward was allowing a nurse to check his vital signs and recorded them to an electronic file of his medical record, which was later retrieved by the specialist he saw.

As it turned out, the specialist ruled it was acute gastroenteritis that caused his illness and the doctor wanted to follow up on his condition in the next appointment with him.

All new information – the new diagnosis, laboratory test results, new medicines prescribed and the new appointment – was immediately sent online to both the clinic and the patient’s smartphone.

And that is how the so-called e-Referral system, launched in 2016 and now linked also with the BAH Connect mobile app, of BAH’s primary care network works.

The BAH’s primary care network, operated under the country’s universal health coverage (UHC) scheme that covers about 48 million Thais or about 75% of the entire population, now consists of 25 privately-owned clinics.

The network now takes care of about 150,000 people under the UHC in five northern Bangkok districts, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong Pajaree, director of BAH.

Two clinics had been excluded from the network after they failed an annual health care quality audit, he said.

Back in 2002, the nationwide implementation of the UHC came as a real headache to BAH. As a teritiary referral hospital, BAH didn’t have any general practitioner (GP) but it was required to deliver primary care to patients under the UHC. The reason is it is the only large state-run health care facility in this particular area of the capital.

As soon as the UHC policy was implemented, BAH found its outpatient ward suddenly becoming overcrowded, while its specialists were forced to take an extra workload of primary care services, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

And since BAH is a health care facility of the air force, it isn’t permitted to buy or rent a building to set up its own primary health care facilities outside air force’ areas, he said.

“We had trouble trying to cope with these problems for many years. The outpatient ward was crowded with 500 to 600 patients a day. No one was happy. There were lots of complaints from both patients and hospital staff,” he said.

Thinking outside the box, he eventually saw a good potential in those many privately-owned clinics and came up with an idea of forming a primary care network with them.

The hospital in the beginning aimed to recruit only between seven and ten clinics into the network; but up to 30 clinics had applied, he said.

A total of 27 clinics were then chosen for implementing the primary care network plan, which began in 2006 and became in full operation in 2007.

These clinics are paid an annual budget of between 700 baht and 1,200 baht per head of the people they take care of under the UHC, said Dr Weraphan Leethanakul, director of the National Health Security Office’s Region 13 office in Bangkok.

The clinics are also entitled to receiving extra budget for additional health promotion and prevention work in communities if they are willing to do, he said.

Prem Pracha Medical Clinic, one of the 25 clinics in the BAH’s primary care network, for instance, now takes care of 9,754 people, or about 18% of the population registered under the UHC in the areas covered by BAH, he said.

Currently, Bangkok has about 279 primary care units and 40 hospitals under the UHC, he said.

With the primary care network in place, the number of outpatients at BAH had dramatically dropped from between 500 and 600 a day to only 80 a day, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

After all, a major problem remained. The hospital still struggled to deal with about 180,000 patient referrals a year. Each referral consumed a lot of time on both the patient and the hospital sides due to the amount of paperwork involved.

“The referral paperwork was something that could actually be completed in a minute; but it in reality took more than an hour to get done at the time,” he said.

BAH had therefore in 2016 begun collaborating with the NHSO and the National Electronics and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC) to develop an electronic patient referral system.

The e-Referral is a cloud-based system that helps cut paperwork and save a great deal of time and money for both patients and the health care facilities, said Sarun Sumriddetchkajorn, a deputy executive director of NECTEC.

As well, the e-Referral system helps cut unnecessary travelling costs of the patients by at least 10 million baht a year and save about 77 minutes per patient in waiting time, said Vice Marshal Taweepong.

BAH now expects to next win permission to gain full access to health care databases of the 25 clinics under its primary care network via the e-Referral system and use artificial intelligence (AI) to better access their health care performance, he said.

“Quality in health care is our goal,” he said.

////////////30 January 2020

A male patient visited a privately-owned clinic in a community in northern Bangkok and complained to a doctor he had suffered abdominal pains for a couple of weeks.

A preliminary diagnosis was diarrhoea; but the doctor still thought the patient needed to consult a specialist at Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital (BAH).

It took the doctor a few minutes to key into his computer the diagnosis, medicines prescribed and a request for an appointment with a specialist for the patient. This information was sent online instantly as soon as the doctor pressed the save and send buttons on the computer’s screen.

The patient got his medicines and went home waiting for a notification to be sent to his smartphone regarding the confirmation of his appointment with a specialist at BAH. The information recorded at the clinic about the diagnosis of his illness and medicines prescribed were already sent to his phone via an application called BAH Connect.

Later in the afternoon, when BAH regularly responded to specialist appointment requests received each day, the appointment request sent by the clinic was confirmed. The confirmed appointment was instantly sent to the clinic and the patient online.

The following day, the patient visited BAH without having to go back to the clinic for a referral document. And all he had to do at the hospital’s outpatient ward was allowing a nurse to check his vital signs and recorded them to an electronic file of his medical record, which was later retrieved by the specialist he saw.

As it turned out, the specialist ruled it was acute gastroenteritis that caused his illness and the doctor wanted to follow up on his condition in the next appointment with him.

All new information – the new diagnosis, laboratory test results, new medicines prescribed and the new appointment – was immediately sent online to both the clinic and the patient’s smartphone.

And that is how the so-called e-Referral system, launched in 2016 and now linked also with the BAH Connect mobile app, of BAH’s primary care network works.

The BAH’s primary care network, operated under the country’s universal health coverage (UHC) scheme that covers about 48 million Thais or about 75% of the entire population, now consists of 25 privately-owned clinics.

The network now takes care of about 150,000 people under the UHC in five northern Bangkok districts, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong Pajaree, director of BAH.

Two clinics had been excluded from the network after they failed an annual health care quality audit, he said.

Back in 2002, the nationwide implementation of the UHC came as a real headache to BAH. As a teritiary referral hospital, BAH didn’t have any general practitioner (GP) but it was required to deliver primary care to patients under the UHC. The reason is it is the only large state-run health care facility in this particular area of the capital.

As soon as the UHC policy was implemented, BAH found its outpatient ward suddenly becoming overcrowded, while its specialists were forced to take an extra workload of primary care services, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

And since BAH is a health care facility of the air force, it isn’t permitted to buy or rent a building to set up its own primary health care facilities outside air force’ areas, he said.

“We had trouble trying to cope with these problems for many years. The outpatient ward was crowded with 500 to 600 patients a day. No one was happy. There were lots of complaints from both patients and hospital staff,” he said.

Thinking outside the box, he eventually saw a good potential in those many privately-owned clinics and came up with an idea of forming a primary care network with them.

The hospital in the beginning aimed to recruit only between seven and ten clinics into the network; but up to 30 clinics had applied, he said.

A total of 27 clinics were then chosen for implementing the primary care network plan, which began in 2006 and became in full operation in 2007.

These clinics are paid an annual budget of between 700 baht and 1,200 baht per head of the people they take care of under the UHC, said Dr Weraphan Leethanakul, director of the National Health Security Office’s Region 13 office in Bangkok.

The clinics are also entitled to receiving extra budget for additional health promotion and prevention work in communities if they are willing to do, he said.

Prem Pracha Medical Clinic, one of the 25 clinics in the BAH’s primary care network, for instance, now takes care of 9,754 people, or about 18% of the population registered under the UHC in the areas covered by BAH, he said.

Currently, Bangkok has about 279 primary care units and 40 hospitals under the UHC, he said.

With the primary care network in place, the number of outpatients at BAH had dramatically dropped from between 500 and 600 a day to only 80 a day, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

After all, a major problem remained. The hospital still struggled to deal with about 180,000 patient referrals a year. Each referral consumed a lot of time on both the patient and the hospital sides due to the amount of paperwork involved.

“The referral paperwork was something that could actually be completed in a minute; but it in reality took more than an hour to get done at the time,” he said.

BAH had therefore in 2016 begun collaborating with the NHSO and the National Electronics and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC) to develop an electronic patient referral system.

The e-Referral is a cloud-based system that helps cut paperwork and save a great deal of time and money for both patients and the health care facilities, said Sarun Sumriddetchkajorn, a deputy executive director of NECTEC.

As well, the e-Referral system helps cut unnecessary travelling costs of the patients by at least 10 million baht a year and save about 77 minutes per patient in waiting time, said Vice Marshal Taweepong.

BAH now expects to next win permission to gain full access to health care databases of the 25 clinics under its primary care network via the e-Referral system and use artificial intelligence (AI) to better access their health care performance, he said.

“Quality in health care is our goal,” he said.

////////////30 January 2020

RESOURCE CENTER

SECRETARY-GENERAL

Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital ensures health care quality with innovations, technology

Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital ensures health care quality with innovations, technology

A male patient visited a privately-owned clinic in a community in northern Bangkok and complained to a doctor he had suffered abdominal pains for a couple of weeks.

A preliminary diagnosis was diarrhoea; but the doctor still thought the patient needed to consult a specialist at Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital (BAH).

It took the doctor a few minutes to key into his computer the diagnosis, medicines prescribed and a request for an appointment with a specialist for the patient. This information was sent online instantly as soon as the doctor pressed the save and send buttons on the computer’s screen.

The patient got his medicines and went home waiting for a notification to be sent to his smartphone regarding the confirmation of his appointment with a specialist at BAH. The information recorded at the clinic about the diagnosis of his illness and medicines prescribed were already sent to his phone via an application called BAH Connect.

Later in the afternoon, when BAH regularly responded to specialist appointment requests received each day, the appointment request sent by the clinic was confirmed. The confirmed appointment was instantly sent to the clinic and the patient online.

The following day, the patient visited BAH without having to go back to the clinic for a referral document. And all he had to do at the hospital’s outpatient ward was allowing a nurse to check his vital signs and recorded them to an electronic file of his medical record, which was later retrieved by the specialist he saw.

As it turned out, the specialist ruled it was acute gastroenteritis that caused his illness and the doctor wanted to follow up on his condition in the next appointment with him.

All new information – the new diagnosis, laboratory test results, new medicines prescribed and the new appointment – was immediately sent online to both the clinic and the patient’s smartphone.

And that is how the so-called e-Referral system, launched in 2016 and now linked also with the BAH Connect mobile app, of BAH’s primary care network works.

The BAH’s primary care network, operated under the country’s universal health coverage (UHC) scheme that covers about 48 million Thais or about 75% of the entire population, now consists of 25 privately-owned clinics.

The network now takes care of about 150,000 people under the UHC in five northern Bangkok districts, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong Pajaree, director of BAH.

Two clinics had been excluded from the network after they failed an annual health care quality audit, he said.

Back in 2002, the nationwide implementation of the UHC came as a real headache to BAH. As a teritiary referral hospital, BAH didn’t have any general practitioner (GP) but it was required to deliver primary care to patients under the UHC. The reason is it is the only large state-run health care facility in this particular area of the capital.

As soon as the UHC policy was implemented, BAH found its outpatient ward suddenly becoming overcrowded, while its specialists were forced to take an extra workload of primary care services, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

And since BAH is a health care facility of the air force, it isn’t permitted to buy or rent a building to set up its own primary health care facilities outside air force’ areas, he said.

“We had trouble trying to cope with these problems for many years. The outpatient ward was crowded with 500 to 600 patients a day. No one was happy. There were lots of complaints from both patients and hospital staff,” he said.

Thinking outside the box, he eventually saw a good potential in those many privately-owned clinics and came up with an idea of forming a primary care network with them.

The hospital in the beginning aimed to recruit only between seven and ten clinics into the network; but up to 30 clinics had applied, he said.

A total of 27 clinics were then chosen for implementing the primary care network plan, which began in 2006 and became in full operation in 2007.

These clinics are paid an annual budget of between 700 baht and 1,200 baht per head of the people they take care of under the UHC, said Dr Weraphan Leethanakul, director of the National Health Security Office’s Region 13 office in Bangkok.

The clinics are also entitled to receiving extra budget for additional health promotion and prevention work in communities if they are willing to do, he said.

Prem Pracha Medical Clinic, one of the 25 clinics in the BAH’s primary care network, for instance, now takes care of 9,754 people, or about 18% of the population registered under the UHC in the areas covered by BAH, he said.

Currently, Bangkok has about 279 primary care units and 40 hospitals under the UHC, he said.

With the primary care network in place, the number of outpatients at BAH had dramatically dropped from between 500 and 600 a day to only 80 a day, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

After all, a major problem remained. The hospital still struggled to deal with about 180,000 patient referrals a year. Each referral consumed a lot of time on both the patient and the hospital sides due to the amount of paperwork involved.

“The referral paperwork was something that could actually be completed in a minute; but it in reality took more than an hour to get done at the time,” he said.

BAH had therefore in 2016 begun collaborating with the NHSO and the National Electronics and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC) to develop an electronic patient referral system.

The e-Referral is a cloud-based system that helps cut paperwork and save a great deal of time and money for both patients and the health care facilities, said Sarun Sumriddetchkajorn, a deputy executive director of NECTEC.

As well, the e-Referral system helps cut unnecessary travelling costs of the patients by at least 10 million baht a year and save about 77 minutes per patient in waiting time, said Vice Marshal Taweepong.

BAH now expects to next win permission to gain full access to health care databases of the 25 clinics under its primary care network via the e-Referral system and use artificial intelligence (AI) to better access their health care performance, he said.

“Quality in health care is our goal,” he said.

////////////30 January 2020

A male patient visited a privately-owned clinic in a community in northern Bangkok and complained to a doctor he had suffered abdominal pains for a couple of weeks.

A preliminary diagnosis was diarrhoea; but the doctor still thought the patient needed to consult a specialist at Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital (BAH).

It took the doctor a few minutes to key into his computer the diagnosis, medicines prescribed and a request for an appointment with a specialist for the patient. This information was sent online instantly as soon as the doctor pressed the save and send buttons on the computer’s screen.

The patient got his medicines and went home waiting for a notification to be sent to his smartphone regarding the confirmation of his appointment with a specialist at BAH. The information recorded at the clinic about the diagnosis of his illness and medicines prescribed were already sent to his phone via an application called BAH Connect.

Later in the afternoon, when BAH regularly responded to specialist appointment requests received each day, the appointment request sent by the clinic was confirmed. The confirmed appointment was instantly sent to the clinic and the patient online.

The following day, the patient visited BAH without having to go back to the clinic for a referral document. And all he had to do at the hospital’s outpatient ward was allowing a nurse to check his vital signs and recorded them to an electronic file of his medical record, which was later retrieved by the specialist he saw.

As it turned out, the specialist ruled it was acute gastroenteritis that caused his illness and the doctor wanted to follow up on his condition in the next appointment with him.

All new information – the new diagnosis, laboratory test results, new medicines prescribed and the new appointment – was immediately sent online to both the clinic and the patient’s smartphone.

And that is how the so-called e-Referral system, launched in 2016 and now linked also with the BAH Connect mobile app, of BAH’s primary care network works.

The BAH’s primary care network, operated under the country’s universal health coverage (UHC) scheme that covers about 48 million Thais or about 75% of the entire population, now consists of 25 privately-owned clinics.

The network now takes care of about 150,000 people under the UHC in five northern Bangkok districts, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong Pajaree, director of BAH.

Two clinics had been excluded from the network after they failed an annual health care quality audit, he said.

Back in 2002, the nationwide implementation of the UHC came as a real headache to BAH. As a teritiary referral hospital, BAH didn’t have any general practitioner (GP) but it was required to deliver primary care to patients under the UHC. The reason is it is the only large state-run health care facility in this particular area of the capital.

As soon as the UHC policy was implemented, BAH found its outpatient ward suddenly becoming overcrowded, while its specialists were forced to take an extra workload of primary care services, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

And since BAH is a health care facility of the air force, it isn’t permitted to buy or rent a building to set up its own primary health care facilities outside air force’ areas, he said.

“We had trouble trying to cope with these problems for many years. The outpatient ward was crowded with 500 to 600 patients a day. No one was happy. There were lots of complaints from both patients and hospital staff,” he said.

Thinking outside the box, he eventually saw a good potential in those many privately-owned clinics and came up with an idea of forming a primary care network with them.

The hospital in the beginning aimed to recruit only between seven and ten clinics into the network; but up to 30 clinics had applied, he said.

A total of 27 clinics were then chosen for implementing the primary care network plan, which began in 2006 and became in full operation in 2007.

These clinics are paid an annual budget of between 700 baht and 1,200 baht per head of the people they take care of under the UHC, said Dr Weraphan Leethanakul, director of the National Health Security Office’s Region 13 office in Bangkok.

The clinics are also entitled to receiving extra budget for additional health promotion and prevention work in communities if they are willing to do, he said.

Prem Pracha Medical Clinic, one of the 25 clinics in the BAH’s primary care network, for instance, now takes care of 9,754 people, or about 18% of the population registered under the UHC in the areas covered by BAH, he said.

Currently, Bangkok has about 279 primary care units and 40 hospitals under the UHC, he said.

With the primary care network in place, the number of outpatients at BAH had dramatically dropped from between 500 and 600 a day to only 80 a day, said Air Vice Marshal Taweepong.

After all, a major problem remained. The hospital still struggled to deal with about 180,000 patient referrals a year. Each referral consumed a lot of time on both the patient and the hospital sides due to the amount of paperwork involved.

“The referral paperwork was something that could actually be completed in a minute; but it in reality took more than an hour to get done at the time,” he said.

BAH had therefore in 2016 begun collaborating with the NHSO and the National Electronics and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC) to develop an electronic patient referral system.

The e-Referral is a cloud-based system that helps cut paperwork and save a great deal of time and money for both patients and the health care facilities, said Sarun Sumriddetchkajorn, a deputy executive director of NECTEC.

As well, the e-Referral system helps cut unnecessary travelling costs of the patients by at least 10 million baht a year and save about 77 minutes per patient in waiting time, said Vice Marshal Taweepong.

BAH now expects to next win permission to gain full access to health care databases of the 25 clinics under its primary care network via the e-Referral system and use artificial intelligence (AI) to better access their health care performance, he said.

“Quality in health care is our goal,” he said.

////////////30 January 2020

VIDEOS

Thailand's UHC Journey

UHC Public relations